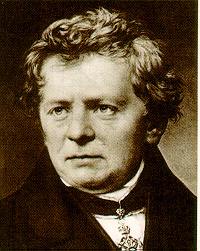

Georg Simon Ohm (1787-1854)

Georg Simon Ohm was a German physicist born in Erlangen, Bavaria, on

March 16, 1787. As a high school teacher, Ohm started his research

with the recently invented electrochemical

cell, invented by Italian Count Alessandro

Volta. Using equipment of his own creation,

Ohm determined that the current that flows through a wire is proportional to

its cross sectional area and inversely proportional to its length or

Ohm's law.

Georg Simon Ohm was a German physicist born in Erlangen, Bavaria, on

March 16, 1787. As a high school teacher, Ohm started his research

with the recently invented electrochemical

cell, invented by Italian Count Alessandro

Volta. Using equipment of his own creation,

Ohm determined that the current that flows through a wire is proportional to

its cross sectional area and inversely proportional to its length or

Ohm's law.

Using the results of his experiments, Georg Simon Ohm was able to define the fundamental relationship between voltage, current, and resistance. These fundamental relationships are of such great importance, that they represent the true beginning of electrical circuit analysis.

Unfortunately, when Ohm published his finding in 1827, his ideas were dismissed by his colleagues. Ohm was forced to resign from his high-school teaching position and he lived in poverty and shame until he accepted a position at Nüremberg in 1833 and although this gave him the title of professor, it was still not the university post for which he had strived all his life.

Ohm’s main interest was current electricity, which had recently been advanced by Alessandro Volta’s invention of the battery. Ohm made only a modest living and as a result his experimental equipment was primitive. Despite this, he made his own metal wire, producing a range of thickness and lengths of remarkable consistent quality. The nine years he spent at the Jesuit’s college, he did considerable experimental research on the nature of electric circuits. He took considerable pains to be brutally accurate with every detail of his work. In 1827, he was able to show from his experiments that there was a simple relationship between resistance, current and voltage.

Ohm’s law stated that the amount of steady current through a material is directly proportional to the voltage across the material, for some fixed temperature:

I = V/R

Ohm had discovered the distribution of electromotive force in an electrical circuit, and had established a definite relationship connecting resistance, electromotive force and current strength.

Ohm the Genius! the Mozart of Electricity ...

Ohm and corrosion monitoring

Ohm was afraid that the purely experimental basis of his work would undermine the importance of his discovery. He tried to state his law theoretically but his rambling mathematically proofs made him an object of ridicule. In the years that followed, Ohm lived in poverty, tutoring privately in Berlin. He would receive no credit for his findings until he was made director of the Polytechnic School of Nüremberg in 1833. In 1841, the Royal Society in London recognized the significance of his discovery and awarded him the Copley medal. The following year, they admitted him as a member. In 1849, just 5 years before his death, Ohm’s lifelong dream was realized when he was given a professorship of Experimental Physics at the University of Munich. On July 7th,1854 he passed away in Munich, at the age of 65.

This belated recognition was welcome but there remains the question of why someone who today is a household name for his important contribution struggled for so long to gain acknowledgement. This may have no simple explanation but rather be the result of a number of different contributory factors. One factor may have been the inwardness of Ohm's character while another was certainly his mathematical approach to topics which at that time were studied in his country a non-mathematical way. There was undoubtedly also personal disputes with the men in power which did Ohm no good at all. He certainly did not find favor with Johannes Schultz who was an influential figure in the ministry of education in Berlin, and with Georg Friedrich Pohl, a professor of physics in that city.

Electricity was not the only topic on which Ohm undertook research, and not the only topic in which he ended up in controversy. In 1843 he stated the fundamental principle of physiological acoustics, concerned with the way in which one hears combination tones. However the assumptions which he made in his mathematical derivation were not totally justified and this resulted in a bitter dispute with the physicist August Seebeck. He succeeded in discrediting Ohm's hypothesis and Ohm had to acknowledge his error.

Connect with us

Contact us today